How to Choose Your Chosen One

/Everyone wants to be special, at least a little bit. We want to believe that the world really does revolve around us and that we’re here for some great purpose. Luckily for us, we can project our desires onto fictional characters.

Enter, Chosen Ones—characters that are literally chosen for greatness. They are typically the protagonist and have been selected to perform heroic deeds. However, there are many different ways to actually be Chosen, and the method often impacts what sort of character they become. So, which version should you choose? Let’s examine three of the most popular versions.

Chosen by Prophecy

In the Harry Potter series, prophecy states that “the one with the power to vanquish the Dark Lord” will be born under very specific circumstances, and he is seemingly the one that must kill Voldemort. Enter... well, Harry Potter. His birth matches the prophecy, and he survives an encounter with Voldemort despite being a baby.

That’s good enough for the wizarding world, and they promptly make Harry their official Chosen One. Despite only learning this himself at age 12, practically everyone puts all their hopes on him to defeat Voldemort once and for all. And he does, after a few years and with some help. But that is a lot of pressure to put on one person, especially a child.

Prophecies are tricky business. They usually dictate that a special individual will rise up to do... something. Prophecies are extremely vague and can be interpreted in different ways. Neville Longbottom was just as likely to become the Chosen One, but it was Voldemort’s actions that solidified the true bearer of the prophecy. One thing is for sure: these prophecies will come true in some form, and our Chosen One is going to make it happen.

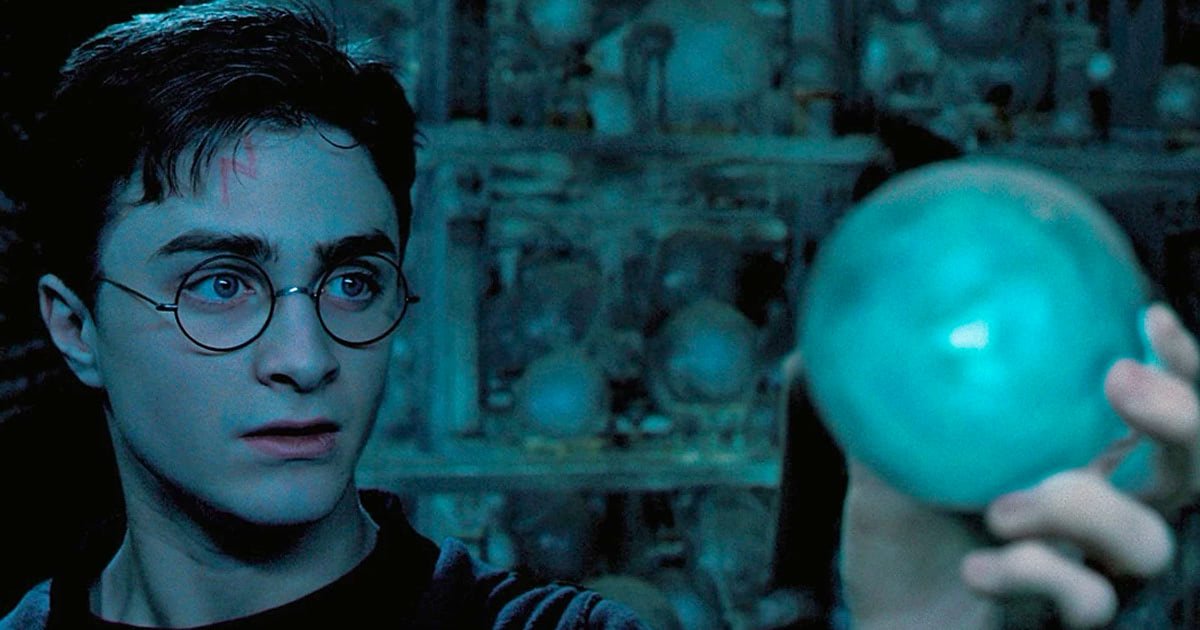

In Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, prophecies are conveniently stored in these ominous orbs.

The Literally Chosen

Unlike winning the magic lottery and being prophesied, these characters are individually selected to become Chosen Ones. It is not fate that chooses, but a specific character like a mentor figure. This chooser has free will and, more importantly, they are not infallible. The Chosen One has no destiny or prophecy to guarantee success—more often than not, they’re just a regular person that is granted power.

One of the most popular examples in recent years comes from My Hero Academia. Izuku “Deku” Midoriya is one of the unlucky few not to be blessed with superpowers, or ‘Quirks’. After proving his heroism despite this, he is gifted a Quirk by legendary hero All Might.

Because their power and status is gifted to them, these Chosen Ones are the most likely to try and return it. Deku tries to pass on his Quirk to others he believes are more worthy on several occasions. These Chosen Ones are different from other iterations due to the fact that they were personally chosen, not by destiny or reincarnation. Speaking of...

Despite appearances, there two are some of the most powerful characters in My Hero Academia

The Chosen Incarnation

These Chosen Ones are less random than others. They are regularly reincarnated in the world to fulfill their duty—usually a general ‘fight evil’ gig—and will be replaced with a new iteration upon death.

In the Avatar universe, the Avatar is a figure that can control the four elements, and their duty is to keep peace between the nations and maintain balance. Aang, the Avatar in The Last Airbender, is a twelve-year-old boy that must end a hundred-year war. Maintaining peace of the entire world is a lot to put on one individual, no matter how strong they are.

Reincarnated Chosen Ones have even more stress than other Chosen Ones. Not only do they have a massive life-long duty, but they also have the extremely high expectations set by all of their previous incarnations to live up to. No pressure.

The Four Seasons, by Scott Wade. A depiction of the Avatar cycle.

By its nature the Chosen One trope heavily impacts both the plot it’s featured in, and the characterization of your Chosen One. Typically, your Chosen One will face serious self-doubt throughout their story—there’s about a 99% chance they will at some point shout “I never asked for this!” Likewise, the broad strokes of the story are generally the same. The story often starts with the Chosen One’s discovery and often ends when they’ve fulfilled their Chosen Duty.

But no two Chosen Ones are the same. Even in Avatar, Aang and the next iteration Korra have very little in common besides being the Avatar. Practically the only thing the three stories we discussed have in common is their protagonists being Chosen Ones.

Being Chosen should be an important part of your character and story, but it doesn’t have to be the only part. There are countless ways to create a Chosen One, so find what works best for you. You can choose your own destiny.

Cor O’Neill

Cor is a Professional Writing student at Algonquin and a horror enthusiast. If he’s not working at the library or attending class, he’s usually creating in some form. He writes in a wide variety of genres and his life dream is to meet Mothman.