Unpacking

/After a couple months in El Salvador and backpacking in Guatemala, my return to Canada was a huge culture shock… more of a shock than my first few days abroad. Everything seemed extravagant when I returned, like seat-belts (chicken buses don’t have seat-belts; nor do the back of the pickup trucks we’d hitch rides on).

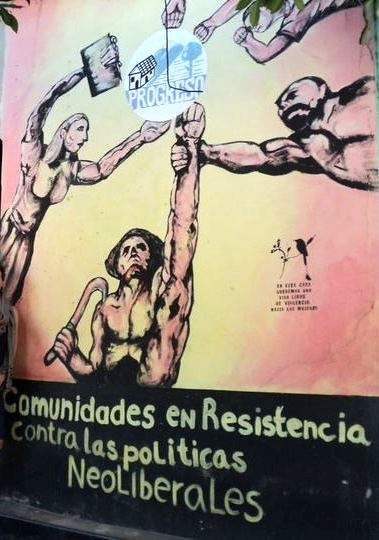

I know Canada gives me so much that I take for granted. But what is harder to cope with is my realization that my life here does directly impact the lives of those I met on my travels. It is because of the wealth and luxury of where I come from that they are deadlocked in a struggle for the right to their own resources. That violence still exists because of the interests of our corporations. That greed, money, and power do have direct consequences for many.

Although I was vaguely aware of this, I now carry stories with me of people who have suffered and fought because of these injustices. I can’t reverse that. On a social level, Peggy McIntosh says we must unpack our “invisible knapsacks” to understand our privileges and how we benefit from them. If we are so lucky to not need to be aware of a reality for our survival, that is considered a privilege. The saying “ignorance is bliss” takes on a whole new level of meaning.

While traveling, I met with some of the staff working at Radio Victoria in Victoria, Cabañas, El Salvador. They told us about some of the death threats they’ve received because of their mission to report truths on mining from neighbouring countries. The National Round-Table Against Metallic Mining has also had to deal with these threats. Some of them have abandoned their families for this work, as they do not want to put their partners or children in danger. Some of their co-workers have already been assassinated, or come home to find animals killed on their front stoop. One employee was sent abroad for her safety. One man, Hector, told us how his brother was kidnapped and found dead in a well. He described the evidence of torture they found on his body. And rather than be scared, Hector is more involved than ever in the fight to stop mining.

If mining is allowed in the country, the pollution of water would be devastating for locals. Many would be displaced, again, for open-pit mining sites. And if the economic model follows that of neighbouring countries with mining, no more than 2% of profit made off this sector would stay in the country… the rest would come to us. Many El Salvadorians would not be trained to work these mining sites. In Guatemala and Honduras, many foreigners are brought in to work the sites. Once a site has had its resource drained, the corporation moves on to the next site, leaving a giant pit and environmental destruction in its wake.

Now that I am back, I continue to celebrate the small wins El Salvador has made against OceanaGold. I have worked to educate myself about others on the issues they are facing, while sharing my experience in my travels. This blog is a new way for me to share with you what I have witnessed. I experience weltschmerz, or world pain, now my eyes have been opened to these realities. I actively practice hope and self-care to keep from dwelling on what I sometimes think is a hopeless expectation for a better world.

I thank you for letting me share all this with you. I hope this is only the beginning of a journey towards a more informed world, where social injustices and realities created by current paradigms are rendered visible to all, even those benefiting from exploitation. This is the first step to understanding. And if, like me, you follow global affairs and experience weltschmerz from the things you learn, I have one last resource to share with you.

When things are especially difficult, I find the words of Dr. Cornel West especially helpful. His lens comes from a Christian reality, but his perspective speaks truth to all.

Life is especially complicated in a globalized world. But West presents a solution that is relatively simple—to live lives of truth and justice, we must learn first how we want to die. He believes there is no power greater than love. With a foundation of love and caring for fellow human beings, we will work to be more aware and cause less harm in our approach to life.

Monique Veselovsky

Monique Veselovsky has always loved the art of the story. As an advocate for social justice, she understands the power of storytelling in overcoming difference. Her greatest desire is to create dialogue and share knowledge, for there is no greater story than someone’s lived experience.

She hopes to tell her story here.

Join her on: