Introducing the 'Good for Her' Cinematic Universe

/

The Strong Female Lead

I’m exhausted by the strong female lead.

You know, this fairly new genre, usually inspired by a YA series, led by a kick-ass, witty, and emotionally stunted young woman who exists solely to save the world.

I didn’t always hate them. I was nine years old when I first saw Ellen Ripley annihilate the Alien Queen with a blow torch in one hand and a child in the other, all the while famously screaming, “Get away from her, you Bitch!”

What I felt then, watching wide-eyed as a young girl, was admiration, awe, and euphoria.

Now, whenever I see a bow-toting, gun-fisted female lead, I click, “Do not recommend.”

In the 80s and 90s, women being portrayed as anything other than a “sexy lamp” or sidekick was ground-breaking. Ellen Ripley and Sara Conner were catalysts for empowerment. They were mothers and caretakers but also emboldened with rage and a gun.

They are characters who ignited a long list of movies that Hollywood producers keep excavating probably until it squeezes out the last cent.

I think what they’re missing here is an opportunity to tell stories about women who are interesting. Complicated. Multi-faceted… Psychotic.

We deserve our version of a male power fantasy. Characters who can embody our fantasies of revenge, who aggressively take back their agency. Whose rage can burn down a whole village.

So, that being said, let me introduce you to the “Good for Her” Cinematic Universe.

The Good For Her Cinematic Universe

Deep in the belly of Film Twitter, I was introduced to the “Good for her Cinematic Universe” by @cinematogrxphy

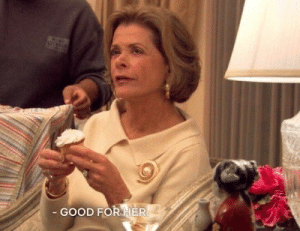

I immediately thought of this meme of Lucille Bluth from Arrested Development listening to an anchorman describe a woman driving her and her children into a lake (probably due to postpartum depression), and she ironically responds with praise.

“Good for her!”

It made me think of some of my favourite films that were all, in some way, horrifying and monstrous. But somehow, Lucille’s morally-questionable voice rang in the back of my mind.

“Good for her!”

Female Rage has been coded as dangerous and destabilizing. The Shrill, Nagging wife. The Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. Feminazis. Racialized women are coded as dangerous even more vigorously.

Our social order is based on this precedent that women must file away their discontent, like putting a lid over a lit candle so that the fire cannot spread.

As William Congreve wrote in The Mourning Bride “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.” While originally about women wronged in love, I think this can be more effectively applied to just about anything else. How society, relationships, religion, and systems can push women to take drastic and unpleasant measures as a means of re-asserting their agency.

Some of my favourite movies of all time fall under The “Good for Her” Cinematic Universe. I didn’t like these movies because they were feminist or politically correct. They definitely shouldn’t be praised for their morale. I just think there is something satisfying about watching a scorned woman get what they want. Kind of like being entranced by a flame that emblazes everything around it.

So many films do this so well: Midsommar, The Witch, Us, Suspiria, but the movie that embodies this genre perfectly is Gone Girl.

“Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.”

In Gone Girl, Amy is compelled to follow her jobless husband, Nick, from the Big City to suburbia. When he fails to be the man she married and she strives to be beautiful, thin, perfect, and appeasing – only for him to find “A younger, bouncier Cool Girl” – her tirade begins.

Amy is a perfect concoction of villainy and female rage. She is a terrifying antagonist fueled by spite, rage and contempt as she meticulously fakes her own violent disappearance to seek revenge on her “lazy, lying, cheating, oblivious husband.” She marvelously pulls off one of the most successful missing person gags in the history of fiction. And she speaks some earth-splitting truths while doing it.

‘The Cool Girl’ Monologue is one of the most iconic monologues of the last decade, mainly due to how relatable it is. The monologue contains many truisms, like how women pretend to be someone they’re not in order to keep the peace in the relationship and to remain desirable to our male counterparts. How women swallow their truth in order to maintain a façade of being unbothered - or cool, so to speak. Like when Nick ditches Amy for a game of poker and doesn’t call or text for hours, and then when he comes home, Amy embraces him and says it’s okay.

Of course, it wasn’t okay. But she lied to keep up with the charade. And this is something we’re all taught to do from a young age. It can file itself under a hefty list of the times we have all made ourselves smaller in order for men to feel more comfortable.

But, her story isn’t supposed to feel good. Amy does a lot of horrible things to get what she wants, and at some point, Amy becomes the “girl who cried rape,” and that certainly doesn’t help the Me Too Movement. She’s not a feminist hero - I mean, she’s literally a psychopath.

When Amy gets everything she wants – her truth just lingers there. And it’s absolutely haunting, horrifying, and holds itself tight to your stomach. She has obliterated the cool girl and turned the strong female lead on its head, and all we can do is stare at the flames.

That’s when that small voice in the back of your mind chimes in.

Alannah Link

Alannah is a writer whose vivid self-awareness often veers into self-consciousness. She can be found either watching the latest A24 flick, spending too much money at the local bookstore, or curating a thematic Spotify playlist.

Blog: TheCrookedFriend