Posted from the Past

/Finding Comfort in the Trenches with Fergus Mackain

“A matter of about five minutes ago Fritz was bombing us, and I have just got up off the ground where I was laying for about twenty minutes. One fellow has been hit, but not severely by shrapnel. This is his second visit this evening.”

See the full transcript of Wiggs’ letter at the UK National Archives website.

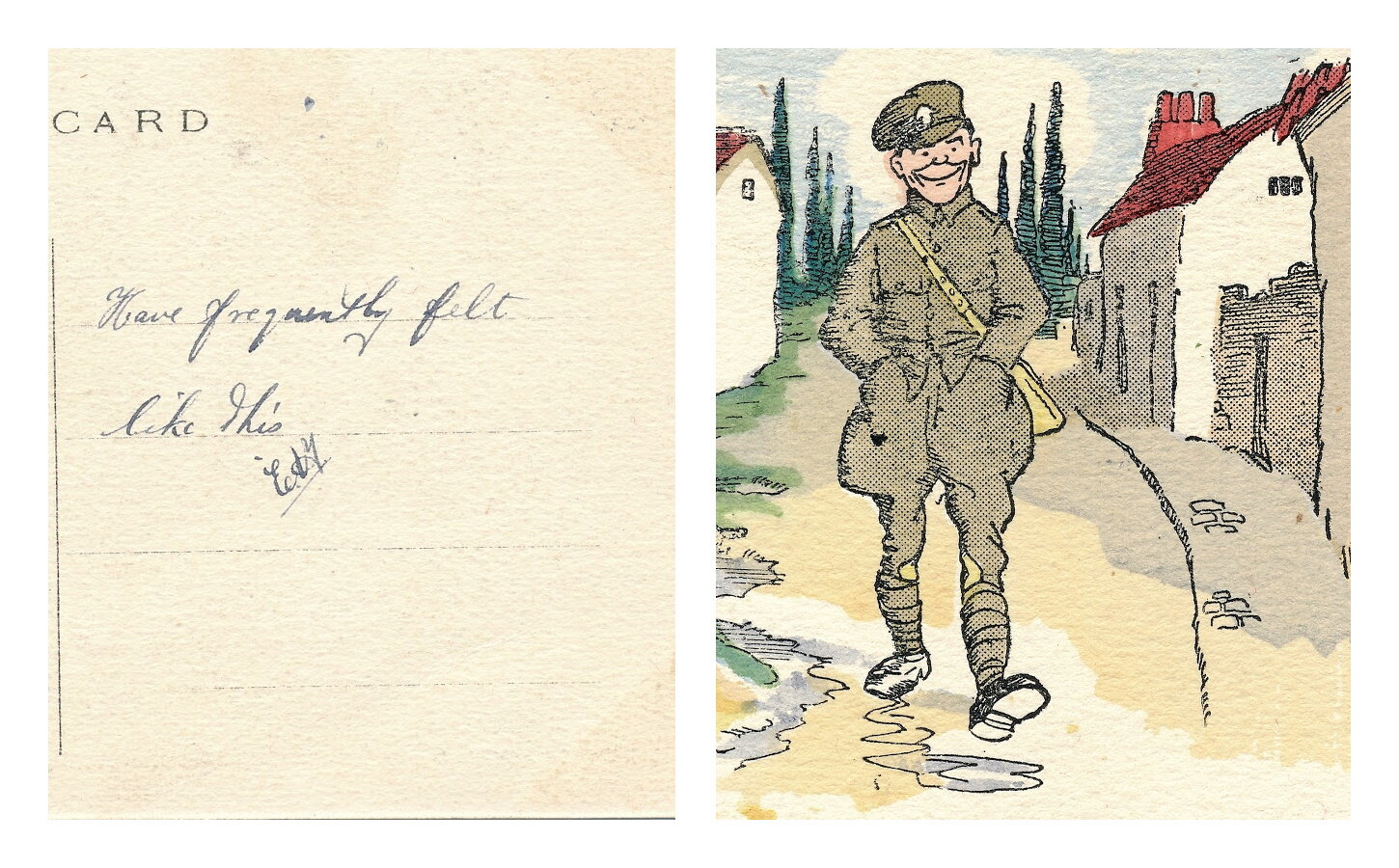

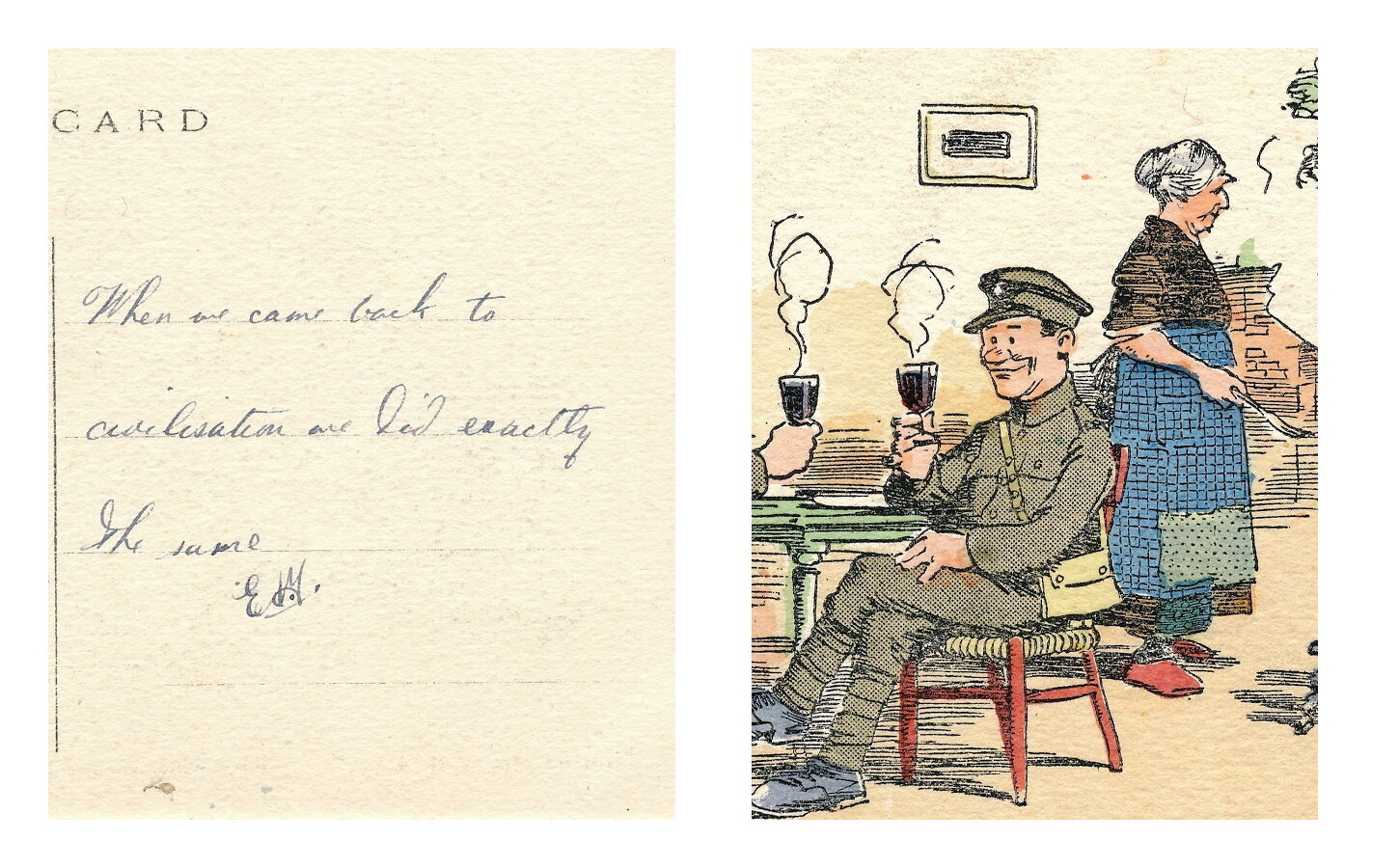

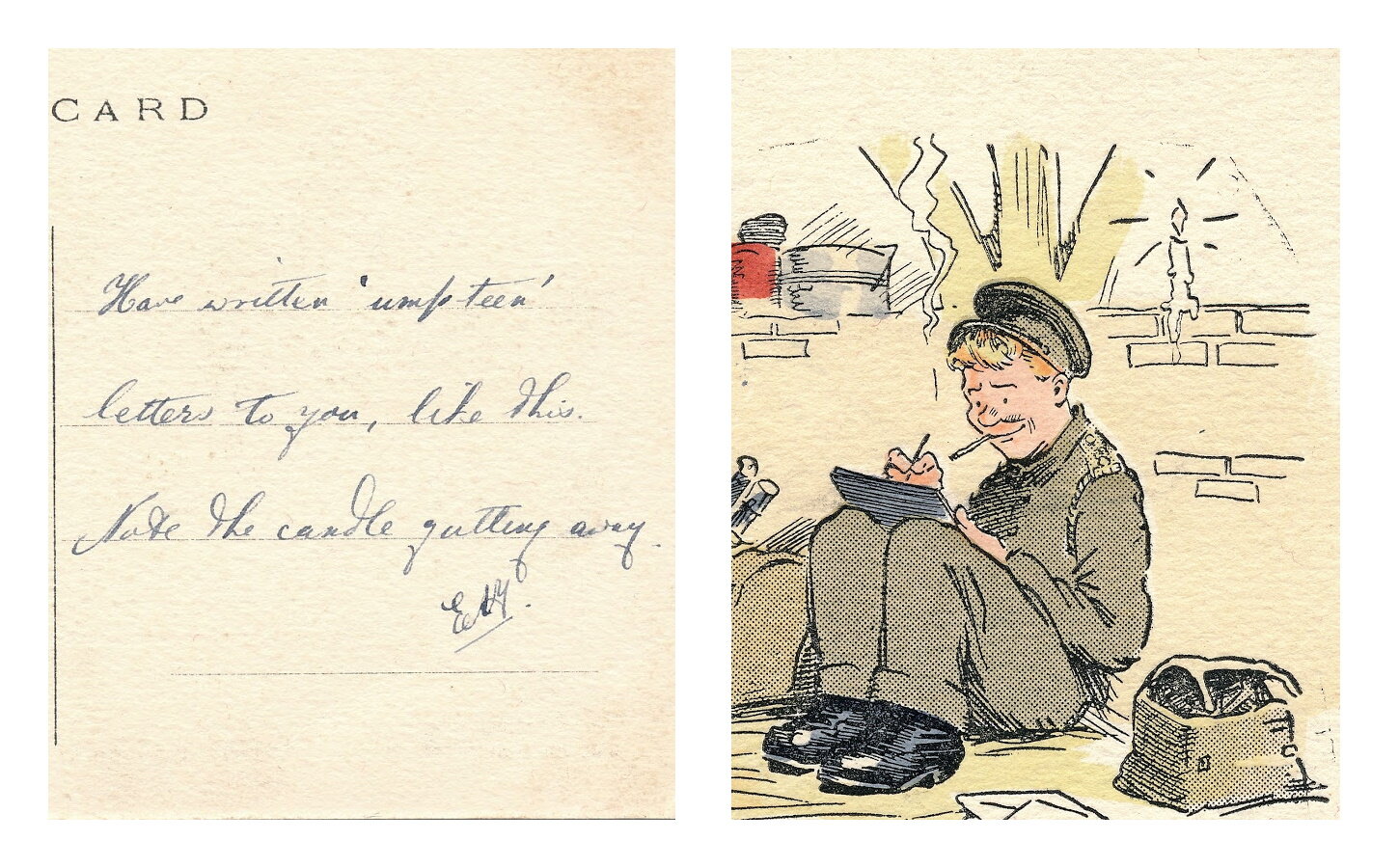

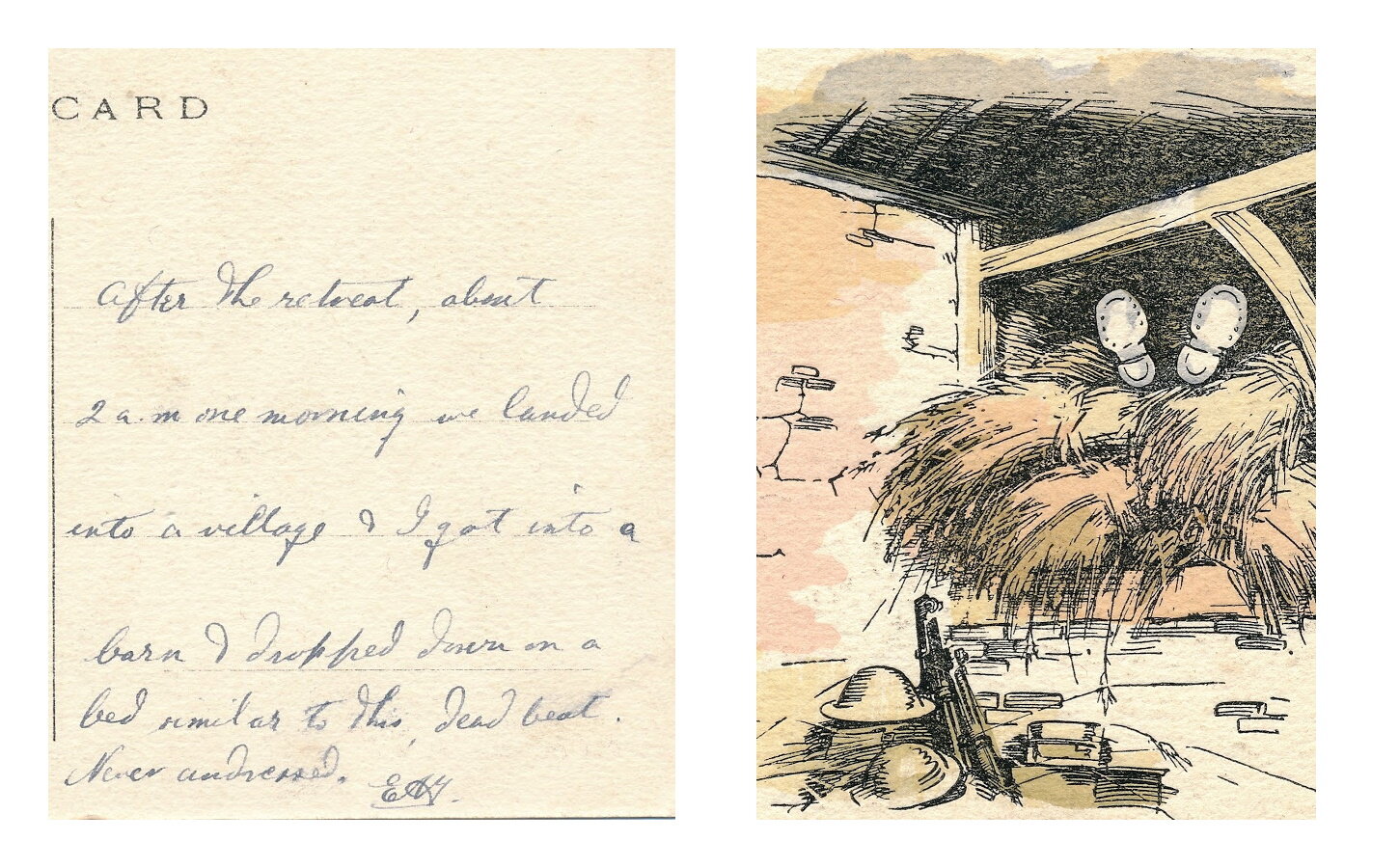

Unsurprisingly, experiences like William Wiggs’ made up the majority of letters written back home to family and friends during the First World War. And though it might be odd to think about, these awful experiences weren’t always taken so seriously. Some experiences were so miserable that only a soldier could laugh about them. Picking up from where we left off in my last post, let’s look at the work of Fergus Mackain, and what role humour played in the life of a soldier.

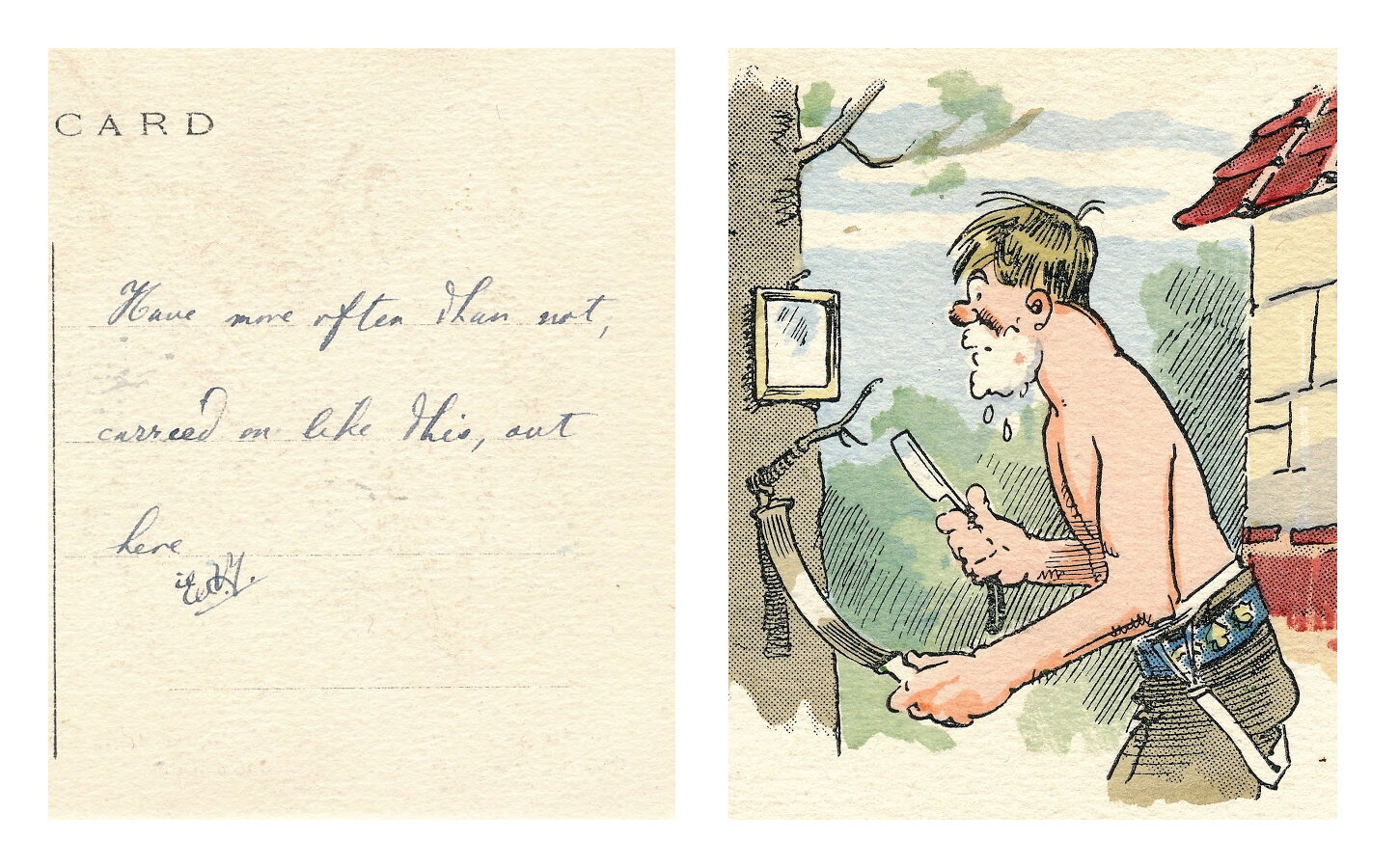

Mackain was born in Saint John, New Brunswick, and worked in the southern United States as an illustrator before enlisting in the British Army in 1915. He served in a regiment that fought at the Somme and Vimy Ridge, survived the war, and returned to the U.S. where he passed away at the age of 38. The series of postcards he created during the war, titled “Sketches of Tommy’s Life,” give us a playful and sometimes morbid take on life in the trenches. What’s striking about Mackain’s art is how well it captured a soldier’s experience, and how it turned miserable situations into something soldiers could joke about as a wartime version of gallows humour.

This can be better attested to by someone who lived through the war. It can be easy to forget, some 100 years later, that these cards weren’t meant as artifacts for us to look back on, but were living objects. A set of Mackain’s artwork belonging to a soldier known only as “E. A. Y.” include his own commentary on how well these cartoons captured a soldier’s experience. Browse the gallery below to see his comments.

There is some support among psychologists that this kind of relatable imagery of shared trauma can act as a sort of glue to bring together a group of people. They helped to build a sense of community among people who have lived similar experiences but would likely never meet face to face. Having these kinds of experiences so succinctly recorded on cards that could be easily circulated between the British soldiers on the Western Front made them the snail-mail version of the relatable internet memes of today. E. A. Y. may as well be posting each image on his Instagram story with the caption, “me lol.”

The thing that has always attracted me to history is its materiality. Ever since I was young, it amazed me that museums just had things on display that people from hundreds, sometimes thousands of years ago created, used, or touched. Objects with a real, tangible connection to history, things that belonged to somebody, are a weird and fascinating insight and intrusion into the essence of a person. Mackain’s art and E. A. Y.’s notes offer rare insight into the lived experience of a soldier and make these postcards unique historical objects.

For more of Fergus Mackain’s art, and a detailed history of his life and work, visit http://www.fergusmackain.com/

Alex Foster-Petrocco

Alex has a BA in History from Carleton and is currently a 2nd-year Professional Writing student at Algonquin.

![“This is one of the truest pictures of life I have seen. It is not exagerated [sic] in the least”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/522614d5e4b02f25c1dfd53c/1605418325335-YRQ556FT8TWNM6NN16GG/OOR5.jpg)